The language of a religion

When the International Energy Agency released its Net Zero by 2050 roadmap earlier last month, it made a splash and it was a loud splash. The authority literally called for the end of oil and gas exploration this year in order for human civilization to achieve a net-zero emission status by 2050.

In more than 200 pages, the IEA detailed “the world’s first comprehensive study of how to transition to a net zero energy system by 2050 while ensuring stable and affordable energy supplies, providing universal energy access, and enabling robust economic growth.”

The report reads a bit like a fairy tale, only unlike a fairy tale it includes statistics and projections. At the same time, it is scarce on specific details that answer the most important question in any major undertaking aimed at effecting massive change: how.

Here’s what the report says about energy intensity, for example, on page 56: “Energy intensity falls by 4% on average each year between 2020 and 2030. This is achieved through a combination of electrification, a push to pursue all energy and materials efficiency opportunities, behavioural changes that reduce demand for energy services, and a major shift away from the traditional use of bioenergy.”

Or take this excerpt about the transportation sector: “In transport, there is a rapid transition away from oil worldwide, which provided more than 90% of fuel use in 2020. In road transport, electricity comes to dominate the sector, providing more than 60% of energy use in 2050, while hydrogen and hydrogen‐based fuels play a smaller role, mainly in fuelling long‐haul heavy‐duty trucks. In shipping, energy efficiency improvements significantly reduce energy needs (especially up to 2030), while advanced biofuels and hydrogen‐based fuels, such as ammonia, increasingly displace oil.”

These two excerpts show something both interesting and worrying. This is the use of the present simple tense for describing future events. Although it’s been two decades since I graduated from university as a BA in English literature and linguistics I vividly remember the many ways we can talk about the future. I also remember that when we use the present simple to refer to future events it is because these events are likely to happen with the highest degree of certainty.

The twist, of course, is that the IEA report does not describe certainties. Far from it, it describes a hypothetical state of affairs whose materialisation would require immense amounts of money, energy, labour, and more money and energy. The choice to describe this hypothetical state of affairs using the present simple makes its net-zero scenario sound a lot more certain, guaranteed, if you will, than it actually is. The IEA roadmap reads like a book from the Bible.

Anyone who’s ever been the object of an insult knows that language has power. Anyone who’s ever studied any religion knows this power is potentially huge. Many energy transition observers on social media mock the use of terms such as “emergency” “disaster” and other emotionally loaded terms to describe the Earth’s climate’s future. These are in turn being mocked for disagreeing with the scientific consensus. I will not be wading into this topic for reasons of self-preservation but I would like to dwell on the use of language in the energy transition and how this use is turning a set of good intentions into what to all intents and purposes is a religion. And religion is a distinctly different phenomenon than science.

“The climate emergency is real. 2020 was the joint warmest year on record. The concentration of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere continues to grow. Sea levels are rising at the same time as the world’s oceans continue to heat up.”

This apocalyptic picture is the introductory paragraph of a white paper by Siemens Gamesa that extols the virtues of green hydrogen: the sort of hydrogen produced through the electrolysis of water using energy generated by solar or wind farms.

Now, white papers are marketing materials so one should always take them with a grain or two of salt. Yet the opening paragraph of this one — like the opening paragraphs of so many other articles, analyses, and forecasts — reads like the start of a religious service. The white paper then goes on to detail why hydrogen and notably green hydrogen is an indispensable part of the energy transition and finally introduces the product it was actually written for.

I’ve written quite a bit about green hydrogen and what its biggest problems are, and the Siemens Gamesa paper acknowledges these. However, like the IEA, it does not answer any of the hows that its report raises.

Here’s what it says about scaling green hydrogen production: “There needs to be a collaborative and joined-up approach between the private sector, governments and public authorities, and investors to overcome the triple challenge of scaling up production which includes:

1. Coordinating efforts to increase installed electrolyzer capacity, which in Europe alone needs to scale up from less than 1GW today to 40GW by 2030; and 500GW by 2050 based on projected investment in production capacities by mid-century.

2. Developing solutions to effectively store, distribute and transport hydrogen, whether in gaseous or liquid form.

3. Putting in place policy frameworks that support and encourage ongoing private sector innovation in green hydrogen while securing future market demand.”

Here’s another paragraph from the same page: “The green hydrogen revolution can only happen if renewable energy deployment is accelerated. By 2050, it’s expected that demand for hydrogen will reach 500 million tonnes. For the majority of this to be met by green hydrogen, it will require between 3,000 and 6,000 GW of new installed renewable capacity, up from 2,800 GW today. Governments need to accelerate their plans, and industry needs to scale its output, production and logistics. As governments around the world look to green the recovery post-pandemic, there is opportunity to do this while benefiting from the wider socio-economic benefits of renewable deployment.”

That’s a lot of things that need to be done and the repeated use of the verb ‘need’ serves to build a sense of urgency, which is why it is used.

These are only a couple of examples on how the official net-zero narrative is shaped. The shape is that of a set of dogma, typical for religious systems and — this is the other twist — similar to steps of the scientific method. The difference between religious dogma and the scientific method is that science continuously questions itself. Dogma bears no questioning, hence the headline of this post.

The need for a buildup in renewable energy generation capacity is unquestionable. So is the need for a buildup in hydrogen production capacity and so is the need for a substantial reduction in oil, coal, and gas production. The fact that the production of solar panels, wind turbines, and electrolysers, among others, is regularly overlooked in net-zero forecasts and roadmaps although it is increasingly often addressed in commentary, such as this one, on the emissions footprint of EV production, for example, or this one, which addresses the land problem with utility-scale solar farms. Or here’s this report, which casts a shadow over the official solar power narrative, which says that costs are on a steady and irreversible way down.

Like established religions, the net-zero narrative is the target of challenges, both from scientists and laypeople, and, as the Reuters report cited above, real life. Also like established religions, the net-zero narrative brushes these off with dogmatic statements that boil down to “There is just no other way to save the planet.”

Indeed, there is another way but that way wins no votes in elections because it comes down to us, as a species, consuming a lot less energy, which is impossible without taking steps some of us remember from totalitarian times. A renewable energy shift is therefore the most plausible — and socially palpable — way to reduce the effects of our energy consumption on our environment, even if it is being spurred on by apocalyptic warnings.

The latest dose of those came from the new IPCC climate report, whose release prompted a flurry of dramatic headlines. The secretary-general of the UN was no less dramatic than media: "This report must sound a death knell for coal and fossil fuels, before they destroy our planet," Antonio Gutteres said in a statement.

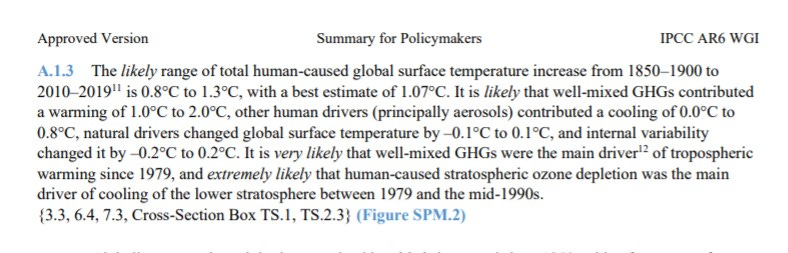

But what about the report itself? The report itself uses quite different language. For one thing — and it is an important thing — the report talks about degrees of likelihood. Here’s a snapshot:

It is no coincidence that the likelies are all italicised. They are essential for conveying the right message, as brought forward by scientists rather than journalists and PR professionals. The thing about science is that few things are ever 100% certain. The ethical thing to do is acknowledge this lack of certainty, even if the degree of likelihood for a causal relation between two events is extremely likely or virtually certain.

This is not to say that the report is not damning. It certainly is. The authors basically say that some of the damage we have inflicted will be lasting. Sadly, the way they are saying this smacks of the religious speak. “The response of biogeochemical cycles to the anthropogenic perturbation can be abrupt at regional scales, and irreversible on decadal to century time scales”.

Now, the word “irreversible” normally implies a permanence to whatever is irreversible. But here we have a temporary irreversibility, which certainly sounds fascinating if a little hard to imagine. What is effectively being said is that we have damaged the planet but it could still fix itself if we stop damaging it. This is the essence of the whole energy transition message, in fact, when we strip it of the dramatic overtones.

Further on, the report mentions that some of the change we’ve made to the Earth’s climate may persist for hundreds or thousands of years, noting the rise in sea level, which starts slowly but continues for quite a while. And then the report says sea levels could rise by as much as 30 m to 1 or even more by the end of this century, which is definitely not “in a while” but rather “very soon.” Of course, the culprit of this superfast rise would be emissions.

The whole report is almost 4,000 pages. The above is only a tiny example of how language could be used even in scientific reports to supercharge a message in a bid to spark action. But the supercharging used in the report pales considerably when compared with the headlines that let the world know about the IPCC’s latest work.

IPCC climate report: Earth is warmer than it’s been in 125,000 years, wrote Nature.

UN’s IPCC report on climate change sounds ‘code red’ for planet, TechCrunch reported, among others who quoted the “code red” reference.

The Guardian picked an even juicier quote: IPCC report shows ‘possible loss of entire countries within the century’.

'Code red for humanity': UN report gives stark warning on climate change, says wild weather events will worsen, warned USA Today.

A Hotter Future Is Certain, Climate Panel Warns. But How Hot Is Up to Us., was The New York Times take on the news.

The list of headlines could go on for a long time. The stories below the headlines unsurprisingly called for the end of fossil fuels right now, just like the IEA Net-Zero Roadmap. Writing a scenario of how a world fueled by a commodity suddenly stops using it would no doubt be an interesting mental exercise. The result, however, would be a horror story.

One might reasonably ask why the effort to turn the transition into a religious belief if it is the only way forwards. The answer is the cost of that transition. Forecasts see it in the tens of trillions of dollars. Then forecasters note that the fallout from the changing climate will cost us even more, so it makes sense to spend these trillions. It does indeed make sense to spend trillions to save three — or five or ten — times as much, although some doubt the cost of anthropogenic climate change is so high.

Yet there seems to be a certain shyness when the question is raised about where these trillions will come from. This shyness also makes sense: the money will have to come, in one way or another, from the regular energy consumer. Creating a sense of urgency and the need to act now to avoid a catastrophe later therefore makes the most sense of all. Anyone would be more willing to pay higher electricity bills if they feel this helps the environment that their children would one day live in.

The above will, to some, sound like yet another portion of climate denialism. Interestingly, from a linguistic perspective, “climate denialism” is a nonsensical phrase. The correct term would be “climate change denialism”, which, however, is also nonsensical. As many a mocked commentator has noted, climate is not immutable. Neither is it immune from human activity, a lot of it destructive for the planet in more than one way. The ways humankind has altered its environment for its own convenience are numerous and go a lot further back than the Industrial Revolution and greenhouse gas emissions.

These numerous ways of humans harming nature have been in the public eye for decades. It was only recently that the emissions narrative became dominant. The reason for this is perfectly simple. Emission reduction through an energy transition is lucrative. Conservation of damaged ecosystems, not so much. Turning business into a religion is perhaps the most ingenious way of securing the sustainability of that business over the long term.