Reality check: fossil fuel prices soar as shortages bite in

Shortage is shaping up to be the word of the year. Everywhere you look, there are shortages: lumber, semiconductors, water, sand, oil, gas, and even coal. Coal demand, in fact, is soaring, carbon footprint and all.

Coal prices have gained 56% over the past 12 months. To a certain extent, this had to do with China’s effective ban on Australian coal, which allowed other suppliers to charge more for their exports to both China and other destinations. But more than this, the coal price rise—64% since the start of 2021—had to do with other factors, such as low investment in new production and tight gas supply.

The interconnected nature of our energy sources is fascinating. Coal has been the main target of emission-reduction efforts for years because of the size of its pollution potential, most of it fully realised. As a result, coal power plants are being retired in a rush and miners are not investing in new production capacity because coal is on its way out forever.

Situations like the one we have right now suggest that noting is final. Europe, the front-runner in the fight for a greener planet, is turning to coal to satisfy its electricity demand. The reason? It’s short on natural gas. The reason for this? A longer and harsher winter that depleted Europe’s gas reserves.

Leaving aside questions about the reliability of renewable energy during seasons of peak energy demand, this problem is unlikely to be solved quickly, either. The winter was long and harsh in Asia, too, and now that continent needs to replenish its reserves as well. As a result, natural gas prices are spiking. In the U.S., grid operators in California and Texas are calling on the locals to prepare to conserve energy and blackouts are being mentioned again.

Oil is also rising. The benchmarks have hit the highest in years as demand for fuels rebounds faster than pretty much everyone expected. In fact, some expected demand for oil would never recover to pre-pandemic levels but now even the IEA expects it to beat these pre-pandemic levels by the end of next year, topping 100 million bpd.

It appears that the world is short on those same fossil fuels that parts of it are trying to phase out and replace with more environmentally friendly alternatives. The world, meaning the people, appears to be fighting back. Or maybe these alternatives have yet to reach a stage of development that makes the three fossil fuels completely replaceable. For now, they aren’t.

Coal use in Europe since the start of the year has jumped by as much as 10-15%, including in Germany, the poster boy for renewables and the most aggressive coal plant retirer. Yet with natural gas reserves running at 25% below the five-year average there appears to be little else to do (except ask Russia for more gas but that would be tricky) than burn more coal.

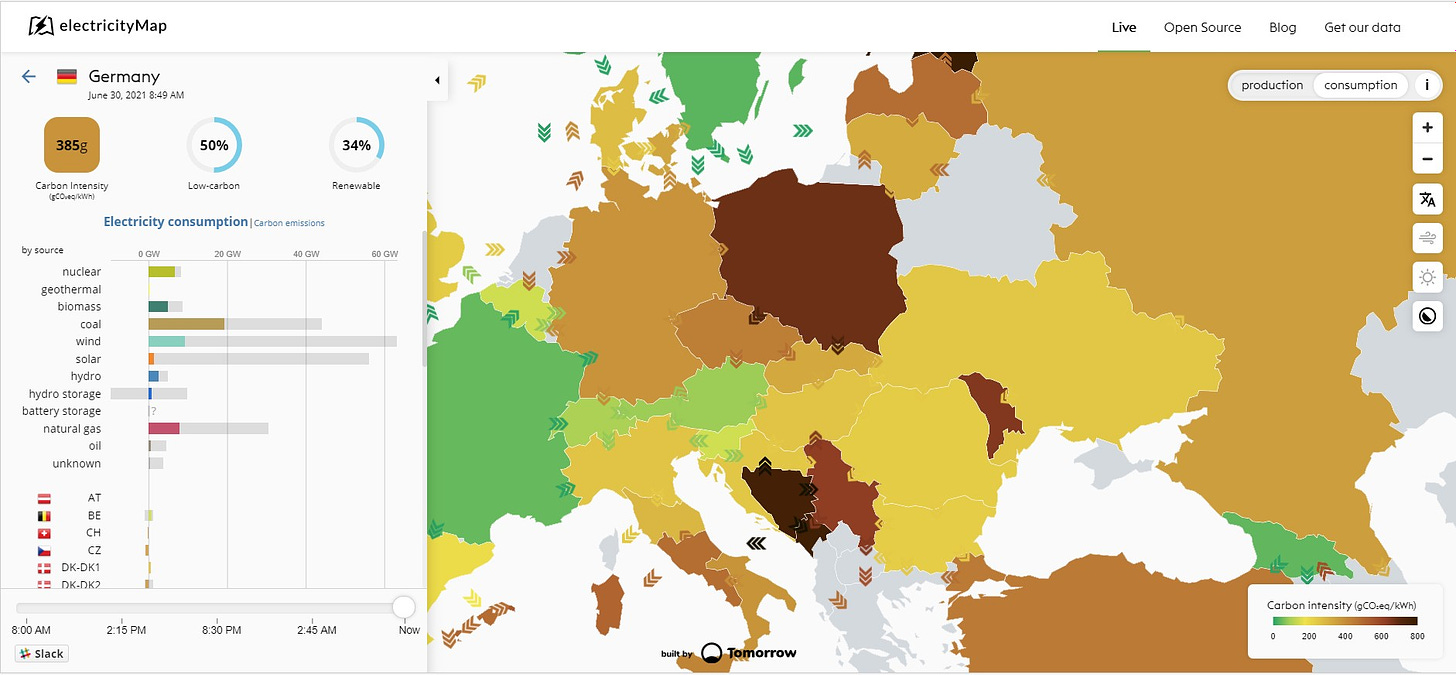

At the time of writing, Germany was getting the biggest portion of its electricity, at 32.86%, from coal plants. Solar accounted for less than 3% of the electricity generation in the country and wind accounted for close to 16% on the last day of June, according to ElectricityMap.

Britain, meanwhile, was getting most of its electricity from natural gas plants and from nuclear plants, the first accounting for close to 40% of total generation on June 30 and the second for a little over 21%. Wind power accounted for 14.7% of total generation and biomass for some 9%.

If the authorities in Brussels have ever needed a reality check — and they do — they have just received it in the form of a cocktail of climate and resources sprinkled with the limits of available energy technology.

Europe has a temperate climate with four seasons. Winter tends to be harsh, which means more energy is consumed. Yet winter conditions are not optimal for solar panels: while the panels like cold, they also like clear skies and a bright sun, which is not the default setting of a European winter. Winter also messes up with wind turbines without special maintenance, which affects the cost of the electricity produced.

Summer, unfortunately, is not ideal, too. It’s got the clear skies and bright sun but it also brings high temperatures and high temperatures significantly compromise solar panel efficiency. Wind droughts also seem to be more frequent during the summer, at least in some parts of Europe and wind droughts mean zero wind power produced.

Meanwhile, coal can burn in any season and so can gas, which is why even net-zero dedicated Europeans are burning them for electricity and contributing to the tight supply brought about in a not insignificant part by these same net-zero ambitions.

One portfolio manager from a low carbon investment fund told Bloomberg earlier this month that whatever politicians do, coal will likely be phased out over the next 10-15 years.

“Politics are important, but you also have the economics of the transition really kicking in within that timeframe,” Ursual Tonkin, from Australian Whitehelm Capital Low Carbon Core Infrastructure Fund, said.

A lot of things may change over the next ten years, this is true enough. Yet looking at the picture today, with solar and wind being hailed as reaching cost parity with coal and gas, but still falling short of meeting increased electricity demand, one would be justified in retaining some scepticism about the phase-out of coal.

In all fairness, there is a shortage of solar panels, too, right now. Rather, global supply chain disruptions are causing delays in raw material deliveries to manufacturing facilities, driving the prices of things such as steel and polysilicon higher.

Polysilicon prices have gone from $6.19 per kilo to as much as $25.88 per kilo over the past year, according to data from BloombergNEF. This is the first time in a decade that solar power prices are on the rise. Few must have expected it — all forecasts for renewable power assume a continuous decline in costs—and now most are unprepared. As a result, many solar farm projects are being delayed because the economics simply doesn’t make sense at the moment.

This may change although predictions are that the supply chain disruptions will likely extend into 2022 as well. This would push back a lot of projects, slowing down the speed of the energy transition and basically wreaking havoc on forecasts. In the meantime, the world will continue guzzling oil, gas, and coal because in the end of the day the way the world works is pretty simple: it needs electricity and it if it doesn’t get it one way or another, there will be trouble for governments.