“Climate activist groups spend a lot of money to inject their message into all media we consume. Whether it’s the movies we watch or the news we read, activists want everyone to be terrified of global warming and to demand transitioning away from fossil fuels.”

This is the opening paragraph of Kevin Killough’s in-depth look at so-called climate fiction, or cli-fi for short — and for same-sounding as sci-fi. The so-called sub-genre has been around for a few years now. It’s trendy among a certain group of authors who seem to have taken it upon themselves to bring the Gospel of Climate Change to innocent readers the world over. Because mandatory gender fluid, non-binary characters weren’t enough of a punishment for the people who like to read.

In his story, Killough notes cli-fi work that’s made it to the New York Times bestseller list. For each of these, there are perhaps dozens of books that will not make it to any bestseller list. But they’ll make it to readers. And they will probably shape worldviews. It won’t be a pretty shape. Because cli-fi is not just thinly to non-veiled climate alarmism propaganda. It’s also bad writing and bad writing fosters bad thinking.

I’ve had a creeping concern about this for a few years now. I’ve been translating books for over 10 years and I’ve noticed a trend. The trend is a shift away from simply telling a story in a compelling way to making a point, nay, Making A Point. The point-making effort is so great, minor details such as grammar, plausibility, and sometimes basic coherence have all taken a back seat, so The Point can take the wheel and floor it.

This hasn’t done wonders for my suspension of disbelief but I’m an old, seasoned reader, as it were. The books I translate are for the young adults among us, and they haven’t had the time to get seasoned. Cli-fi, I suspect, also targets mostly the young adult audience, which makes it extra-bad, in more than one sense of the word.

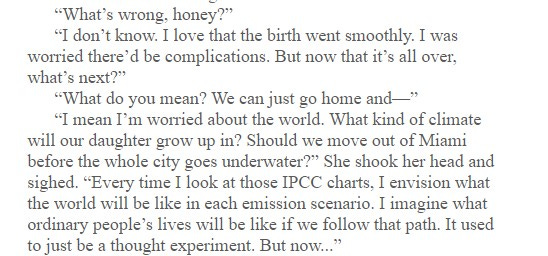

Here’s one quote:

The scene here describes a couple shortly after the birth of their daughter. As we can see, the new mother’s first order of business is to have a grief attack because of IPCC charts. Instead of focusing all her thoughts on the newborn, she worries about the future and Miami sinking. Because that’s totally plausible and not utterly ridiculous at all.

But here’s the problem. This is ridiculous only to actual mothers, fathers, and people with indirect experience of babies. There is no healthy woman who would worry about IPCC charts in the hospital, hours after giving birth — or days, or weeks, or months after that. Indeed, there isn’t a healthy human who’d give emission scenarios any thought when there’s a newborn around. The problem is that there are plenty of unhealthy people out there and some of them, as we can see, are writing books. And books have power.

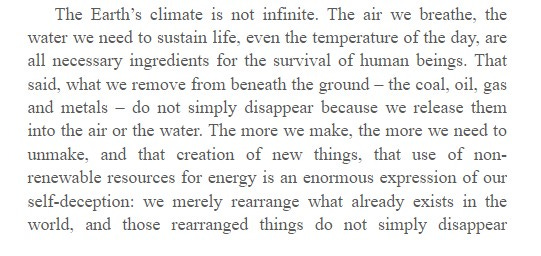

What you and I would see in the excerpt above is shoddy grammar, bad word choice, bad structure, and basically what the hell is this person even talking about, except trying to get the readers to worry. Which is exactly the point. The aim of these works is not story-telling in hopes the story would invoke emotions. The aim is to invoke one single emotion: fear. The aim is to scare readers in a highly specific way — by making them feel guilty about ruining the planet and, hopefully, changing their ways to “unmake” the ruin.

Here’s the problem with that: whether the authors do it deliberately, which I doubt, or inadvertently, they are essentially conditioning their readers to accept ever-greater government intrusion into their daily lives with the purpose of changing these lives for the better of the planet. And that’s because many, if not most, cli-fi authors are in fact climate activists with a flair for the written word.

What we have here is what Kevin Killough warns about in his article: presenting implausible fiction in such a way as to make it sound like fact, which is easier than some might think. A lot easier.

“Our place in the world is shaped by our understanding of the past, and that understanding in turn is shaped by the stories we tell about it. A majority of people in the West get their stories from movies, TV, and fictional accounts rather than true history,” fellow podcaster, energy analyst and voracious reader Tammy Nemeth said, commenting on Kevin’s piece.

Indeed, we are a storytelling species and it is often difficult to distinguish between fact and fiction, especially if the fiction is gripping enough and in tune with our biases and opinions. As the above shows, it doesn’t even need to be particularly good fiction to be gripping and convincing.

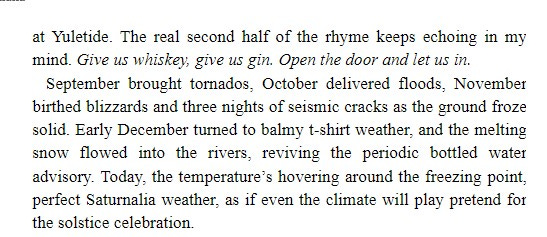

The idea of four seasons squeezed into three months is a stretch, to put it mildly, but would the anxious mind stop to wonder? No, it won’t. Not when it gets bombarded by news headlines about extreme weather on a daily basis. Not when politicians keep harping on about climate change and how it should be number-one priority for all to stop it — by accepting ever-more government intervention and a lower standard of living. For the greater good.

Climate activists claim that climate change must be everywhere — from politics, through education, to entertainment. It’s not everywhere enough, you see, so we have to push it into every single aspect of life, so we can all get The Message. Hence the above-synopsised work, which I admit I didn’t have the courage to leaf through, not after this synopsis.

What we have here is beyond cli-fi. It’s clifantasy of the highest order — it’s got a comic aspect, racial justice or whatever it’s called, mythical creatures, and a mission statement. The comic aspect is especially important — humour can be a tool for making a story more relatable and more interesting, but that very fact can turn it into a powerful weapon for driving a point home. And in the climate change narrative, that’s cause for concern.

Until recently, I assumed that the climate alarmism crowd will be the means of its own destruction because it was incapable of humour. Ridicule they can do, in a low-grade, lame way that’s an insult to the average intellect but since we’re not dealing with average intellect here, low-grade, lame ridicule is the best they can do.

But if climate alarmists have discovered humour, our only hope is that they do comedy as badly as they do scientific research. Because adding humour to climate alarmism narratives makes it a whole lot easier to convince people climate change is a real catastrophic danger. Because humour, and its product comedy, use facts to amuse and entertain us — and teach us important things about life and the state of humanity.

It’s not fiction that makes the basis for comedy. Fiction is the dress comedians don on controversial facts to make them funny and cement them as facts. Long story short, we should be worried about climate change comedy catching on. There’s little chance of that for now, because those activists are really, really seriously concerned about the planet and mad with all of us for driving cars and eating steaks. But if this changes, we’re done for.

I leave you with one of the great comedic minds of our time.

Nearly all things "climate" are really a Trojan horse for the Malthusian Marxist Death Cult to enslave and then eliminate all we free thinkers. Non of this is by default, but all from design. Well done and great article.

Tammy is close to being right but she’s not down to the heart of it. It’s philosophy that drives us and puts us in our place in the world and shapes our understanding of it. Everyone holds philosophy whether they recognize it or not—they either choose ideas consciously or they soak in a mishmash of contradictions from the culture. The way philosophy is communicated to the culture at large is through art (stories, movies, canvas, meme) — these things merely reflect the extent to which bad philosophy has already been inculcated in the minds of the artists, typically by education.